An Early Encounter and Influence

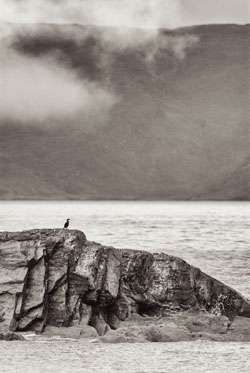

1964, in a quiet bay on Loch Melfort an injured Shag moved awkwardly.Three brothers approached cautiously, for both their own and the bird’s sake. They could touch, stroke and closely observe it in a way that gave real meaning to all those other birds of the Scottish Lochs and hills they had encountered, the ten o’clock Buzzard and the Herons that, in the same fashion as the Shag, suggested to them something pre-historic. It was to be a defining moment for the youngest of the brothers, aged just six.

Early Bird Books

There are other seminal moments in ones upbringing but this still resonates in ways that mark it out from the rest. Perhaps because it was recorded by my dad on 8mm cine film it was more easily brought to mind, but I believe it was more to do with being so close to such a primordial bird that seemed to offer a tangible link to the past and for the first time I remember feeling that there was a link between all life. We were able to individually count its tail feathers, confirming in a taxonomical way, that it was a Shag rather than a Cormorant. I recall looking at the colour plate by A.W. Seaby in ‘British Birds’ by F.B. Kirkman and C.R. Jourdain and being read the opening description on the Shag,

1. Description. – Length, 27 in. Resembles Cormorant in general appearance, but has only 12 tail feathers, is decidedly smaller, and has dark green head, neck and under parts. In spring a curved crest is assumed on the forehead. Male larger; iris green. Young birds have very slender bills; upper parts brownish green; under parts brownish ash, mottled with brown.

This bird book accompanied us along with a couple of others on our holidays in Scotland. It was first published in 1930 but we had a ‘modern’ re-print from 1966. The linking together of the plate, the description and ‘our’ bird was the hook, and I wanted to do it again and again with other birds. Another book that we had with us was the ‘Collins guide to Bird Watching’, by R.S.R. Fitter in 1963. It wasn’t for a six year old but it hinted of what the subject was all about and how much information there was on it, I remember the feeling of excitement of what lay ahead.

We also had a copy of ‘The Oxford Book of Birds’ by Bruce Campbell and Donald Watson. This was more like it for a youngster beginning to feel excited about birds, it was more of a guide and showed the birds in a little of the context you could expect to find them in.

Forty years on

The Shag is also a bird you find on the coast, generally fishing further out than Cormorants and not frequenting estuaries or inland lakes so its romance also lies, for me, in location and habitat as well as within the bird itself. It would be forty years before I would begin to actively photograph birds, but during these intervening years ornithology was always my way to relax and experience the world birds inhabit and to wonder at their extraordinary comings and goings.

I’ve never lost that initial feeling I had when we came across that Shag. Birds continue to inspire and confound and now I’m trying to capture some of this excitement and energy I have felt when in their company through photography.